A Complete Guide to Time Signatures

1. What The Numbers Mean? 🤷🏻

Time signatures are a feature of every piece of music that we read and yet they are often neglected and never fully understood. This is because it’s often thought that time signatures only tell us “how many beats there are in a bar of music”. However, this is not what a time signature actually does! Time signatures are actually much more important then you may think and they are a fundamental part of not only reading rhythms but also understanding how to FEEL the music as they have the import function of telling us which notes to stress and how we should feel the pulse of a piece of music.

The Top Number

But first, let me tell you what a time signature actually is! A time signature is made up of 2 numbers stacked on top of each other and can be found at the beginning of a piece of sheet music.

When reading a time signature; the top number tells us how many notes we are going to be counting in any given bar. This number can be any number but it is most commonly 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 or 12, with the most common number being the number 4!

If the top number in a time signature is a 4 then in our head we will be counting 4 times in the bar (1 2 3 4). If the top number is a 6 then we will be counting 6 times in the bar (1 2 3 4 5 6). If the top number is 2318, then we will be counting 2318 times in the bar (1 2 3 4 5 6 7…..2317 2318 - this example is maybe a little extreme)!

The Bottom Number

The lower number in a time signature tells us what TYPE of notes we are going to be counting. This is the part that many musicians that are new to learning don’t get taught! When we count music, we aren’t actually counting how many beats there are in a bar…we are in fact counting how many of a specific type of note length there are in a bar.

These are much easier to understand in American English rather than European English (correct English 👀) as the lower numbers in a time signature more easily corresponds to the name of the note lengths. If the lower number in a time signature is a 4 then we will be counting quarter notes (crotchets - 1 beat notes). If the lower number in a time signature is an 8 then the type of note we will be counting will be eighth notes (quavers - ½ beat notes).

Here is a list of what numbers the bottom number in a time signature might be:

1 - Whole Notes (Semibreve) - 4 beats long

2 - Half Notes (Minim) - 2 beats long

4 - Quarter Notes (Crotchet) - 1 beat long

8 - Eighth Notes (Quaver) - ½ beat long

16 - Sixteenth Notes (Semiquaver) - ¼ beat long

etc.

This means that if we see a time signature of 4/4 we will be counting “4” “QUARTER NOTES” (crotchets - 1 beat notes) in each bar of the music.

If we see a time signature of 6/8 then we will be counting “6” “EIGHTH NOTES” (quavers - ½ beat notes) in each bar of the music.

A time signature of 224/16 would be “224” “SIXTEENTH NOTES” (semiquavers - ¼ beat notes) in each bar of the sheet music (this would be an odd piece of music!).

2. Counting Time Signatures 🎵

Now that you know what the numbers in a time signature actually mean, we can now use it to help us count the music and this is where time signatures can become very useful (and sometimes very confusing).

Many beginner musicians will be familiar with the time signature of 4/4 and have a stronger understanding of how to count quarter notes (crotchets - 1 beat notes). This is perhaps why many beginners learn that a time signature tells us “how many beats there are in a bar”, because quarter notes (crotchets) last 1 beat each and this seemingly makes sense!

However, thinking this way can make it much more difficult when changing the lower number in a time signature and therefore changing the type of notes that we are going to be counting!

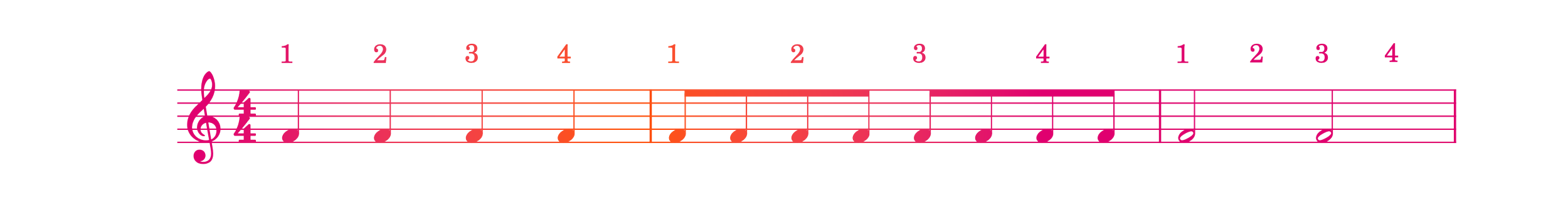

In a time signature of 4/4, we may find a bar of music that simply includes 4 quarter notes (crotchets - 1 beat notes)!

However, if we come across a bar of music that includes eighth notes (quavers - ½ beat notes) then we will be able to fit two of these notes within the time it takes us to count a quarter note (crotchet - 1 beat note). If we have a bar that includes half notes (minims - 2 beat notes), then we will be able to count two numbers per note as these last the length of two quarter notes (crotchets - 1 beat notes).

In a time signature of 6/8, we would need to count the “6” “EIGHTH NOTES” per bar instead. This means that in each bar, quarter notes (crotchets - 1 beat notes) would now last two counts. This is because we are counting every half beat (eight notes/quavers) and a quarter note is twice the length of these. Similarly if we have a bar filled with sixteenth notes (semiquavers - ¼ beat notes), we will now be able to fit 2 of these for each of our counts.

3. Simple and Compound 👨🏻🏫

Time signatures have one last function which becomes incredibly important when feeling the pulse and meter of a piece of music.

You may have noticed that eighth notes (quavers - ½ beat notes) are often grouped together by connecting their tails to form a beam over the notes. The way that these eighth notes (quavers - ½ beat notes) are grouped is actually very intentional and depends on the time signature that we have. They play an important role in how we feel the pulse of a piece of music.

We can categorise time signatures in two ways based on how we group these eighth notes in a bar. Some time signatures group eighth notes (quavers - ½ beat notes) into groups of 2 (and/or 4) and others group eighth notes into groups of 3. If eighth notes are grouped into groups of 2 then we call this a “simple” time signature. If they are grouped into groups of 3 then we call this a “compound” time signature.

We can also determine how many of these groupings will fit in a bar. If a bar will fit 2 groups of 2 eighth notes then this time signature will be a “duple” simple time signature. If a bar will fit 3 groups of 2 eighth notes, then this time signature will be a “triple” simple time signature. If a bar will fit 4 groups of 2 eighth notes, then this time signature will be a “quadruple” simple time signature.

Similarly, if a bar will fit 2 groups of 3 eight notes, then this time signature will be a “duple” compound time signature. If a bar will fit 3 groups of 3 eight notes, then this time signature will be a “triple” compound time signature. If a bar will fit 4 groups of 2 eight notes, then this time signature will be a “quadruple” compound time signature.

The time signature 6/8 therefore means that we are counting “6” “eighth notes” per bar. This time signature is actually a duple compound time signature, meaning we have 2 groups of 3 eighth notes each bar. This means that we will be counting “6” “eighth notes” in each bar, but we will also play this feeling 2 stresses in the bar at the start of each grouping rather than stressing all 6 counts in the bar.

In opposition to this we have the time signature 3/4, which means “3” “quarter notes” per bar. This time signature is a triple simple time signature, meaning that we can fit 3 groups of 2 eighth notes in each bar. This means that we will play this feeling 3 stresses in the bar at the start of each grouping (each beat).

Both 6/8 and 3/4 contain the same number of beats (3/4 = 3 quarter notes, 6/8 = 6 eighth notes), yet we play and feel these two time signatures in very different ways based on the groupings within the bars! In 3/4 we feel 3 stresses within the bar (1 2 3) whereas in 6/8 we feel 2 stresses in the bar (123, 456).

Matthew Cawood

(This is from my “Monday Music Tips“ weekly email newsletter. Join my mailing list to be emailed with future posts.)